The Full Story

“It’s very important that people should know.”

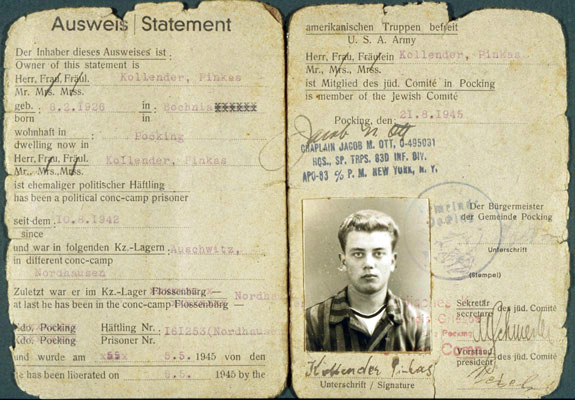

Pincus Kolender was born on February 8, 1926, in Bochnia, Poland, near Krakow. His family was very religious, and as a boy, he attended a Hebrew school, or heder. At that time, of the 25,000 people in Bochnia, 10,000 were Jewish, and while antisemitism was commonplace, Pincus and his family were able to live a quiet life within the Jewish community.

As the Nazis rose to power in neighboring Germany, however, life in Bochnia began to change. Pincus’s father, Chiel,  lost his job in 1936 for refusing to shave his beard. The owner of the store where he worked as an accountant and sales clerk was Jewish himself, but he did not want to risk losing his gentile clientele. Chiel opened a small grocery store on the first floor of the family’s home. Pincus’s mother Rachel helped with the store and took care of their family, which included Pincus, his older brother Abraham, and his older sister Rosa.

lost his job in 1936 for refusing to shave his beard. The owner of the store where he worked as an accountant and sales clerk was Jewish himself, but he did not want to risk losing his gentile clientele. Chiel opened a small grocery store on the first floor of the family’s home. Pincus’s mother Rachel helped with the store and took care of their family, which included Pincus, his older brother Abraham, and his older sister Rosa.

After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Pincus observed the slow infiltration of Nazi rule into his hometown. “It started in 1940. They took their time, the Germans, not right away, gradually, everything was gradually. See, the Germans, they’re masters of deception. They didn’t come in right away and kill Jews. Gradually they took away their businesses, they took away their schools and everything else, and then they put them in the ghettos. Then they closed out the ghettos and put guards around [them] and by then people were trapped.”

Bochnia was transformed into a Jewish ghetto. Ten prominent men were assigned to the Judenrat, or Jewish council, to keep order. The council served as a liaison between the Nazis and the Jews. When the Nazis needed workers from the ghetto, they ordered the Judenrat to round them up.

Chiel Kolender was able to use his friendship with the president of the Judenrat to save his family from being deported to Treblinka. “In 1942, when the last deportation came to our hometown—every few months they had deported the people, either to Auschwitz or Treblinka and so forth. The last deportation we were on the list, too, and my father went to this Symcha Weiss [president of the Judenrat] and he took him off the list. Otherwise we would have gone to Treblinka, too. Treblinka was the one, the extermination camp. From our hometown, they sent them to Treblinka.”

The respite was short-lived. The president of the Judenrat was allowed by the SS to designate 150 people to stay behind to help liquidate the ghetto, but he kept behind many more—about 250. Pincus and his family were among these. When the SS Obersturmfuhrer realized the deception, he angrily ordered his men to choose one hundred people at random. Pincus’s mother was one of the hundred. “They came, they took out my mother and they moved them, a hundred people, about a hundred fifty yards away, lined them up against the wall. We had to watch it and they executed them all and my mother was shot dead. That was September 3, 1942.”

Pincus and his remaining family stayed in the ghetto that had been their home. A year later, his sister, Rosa, was sent to Treblinka. Pincus and his brother, Abraham, were moved to Auschwitz, while his father was sent to nearby Plaszov, a labor camp, where he was shot and killed by the commandant.

Pincus and Abraham were sent to Auschwitz by train. “When we got to Auschwitz, it was dark, it was already night. We didn’t know for a while where we were, but we could see through the window. There was a little bit [of an] opening—it was wired, so nobody could escape—just to give us a little air. We could see Auschwitz. I knew when we could see from the distance its chimneys’ smoke, belching with smoke and fire. You could smell the flesh—it was unbearable—from the human bodies. And gradually, the SS opened up the wagons and they chased us out and we had to get in the line.”

Waiting at the end of this line was Dr. Josef Mengele, who would decide who lived and who died. Before Pincus reached him, he had been warned in Yiddish by an Auschwitz inmate to say he was twenty years old and a carpenter, when he was in fact sixteen years old with no profession. Pincus’s lie did not much help; both he and his brother were sent to the line headed for the gas chambers. “I said to my brother—we didn’t have much time; it was a matter of seconds. I said to him, ‘We’re in the wrong place. Let’s jump, try and get to the other line.’ And here you’ve got SS men in between us with dogs. But we were young and had nothing to lose, and me and my brother, we jumped. I remember the dog ran after me, grabbed me by the butt, bit me. I was too fast for the dog, too. And we got in the other line in split seconds—I mean split seconds, because the line was already finished—and we went into the camp. You see, and that’s why I survived.” Pincus and Abraham both ended up at Buna, the labor camp known as Auschwitz 3, working at the I. G. Farben factory.

A remarkable chain of events in Pincus’s life began on August 20, 1944. An air raid alarm sounded and the SS moved the inmate workers inside the Farben factory buildings before retreating to their underground bunkers. Pincus was grateful for the break from work, a rare opportunity to rest. The break would not last long, however. He heard something that let him know that this was not a drill or false alarm. “Up until now we had a lot of alarms but never, never happen anything. But this time, gradually I could hear from the distance noises, whooo—you could hear mortars, you know. I knew this, and I was right in the middle of the building. It was a big warehouse, probably twenty thousand square feet, and we were about three or four hundred prisoners. My instinct told me we have to live. I said no, I better go to the door. I got up; I remember I even started running, walked over people. Everybody screamed, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ Something told me, and I went to the door and as I went to the door there was a solid hit, a direct hit in the building. And had I, you know, just went to the door, [if] they turned about this way it would have hit me in the mouth, probably would have killed me.”

As it was, Pincus suffered a severe neck wound and lost a great amount of blood. Amazingly, he was not sent to the gas chambers with the seriously wounded, but was taken back into the camp by his friends, who dropped him off at the dispensary that was used as a hospital. He was left there, alone and waiting for attention, for four days. He developed an infection, unable to do anything, even drink or speak. Finally, on the fifth day, he was taken to an operating room and treated by a Jewish surgeon who removed a large splinter from his neck. The surgeon told him he was lucky. “He said another split hair…would have cut my jugular, the main artery, and would have killed me.”

It took two months in the hospital for Pincus to recover. During his recuperation, he discovered that the Jewish surgeon, Dr. Grossman, knew one of Pincus’s uncles in Berlin. This personal connection proved essential to Pincus’s recovery, as he was allowed to remain in the hospital under Dr. Grossman’s care and protection for an extended period of time. “A lot of survivors cannot believe that, because they [typically] didn’t keep you longer than four, five days. If you didn’t [get well], they got rid of you.”

Dr. Grossman came to Pincus after two months to tell him he had to leave. “He called me in his office and he said, “‘Kolender, you [are] better, I’m going to release you. Go on back into the camp, put on your clothes, and I will send an orderly with you.’ And I looked at him. I said, ‘I cannot go back to work.’ I was still so weak. He said, ‘Leave now,’ and he said he’ll give me a letter [to give to the] block—in the barracks.” Though Pincus didn’t understand his removal at the time, it would become clear later that night when the SS evacuated the entire hospital, sending all of the patients to the gas chambers. Dr. Grossman has saved his life a second time.

In January 1945, as the Red Army advanced deeper into Poland, some 60,000 Auschwitz prisoners were forced on a long march away from the camp. Those who survived were sent by freight trains to other camps in Germany. Abraham, Pincus’s brother, died during the march. Pincus survived and made it to Gleiwitz, where he was sent by train to Nordhausen, then Dora, a camp whose inmates were used as slave workers to make German V-2 rockets. Pincus was assigned to a group that drilled tunnels in the mountains at Dora. On April 20, 1945, he was moved again by train to Czechoslovakia.

The train stopped about ten miles outside of Prague. The alarm sounded, and American fighters were soon strafing the railroad with bullets. The two SS men who had been guarding Pincus and the hundred other inmates in his train car took cover beneath the train. Pincus seized his chance. “Instinct told me, you’ve got opportunity now. I knew we were in Czechoslovakia, and I knew Czechoslovakia is a friendly country because they were occupied by the Germans and they hated the Germans, too. So I said, ‘This is the opportunity,’ and another fellow—two fellows of us—we [all] jumped.”

Pincus and two others jumped off the train and ran as fast and as long as they could, narrowly escaping the hail of bullets from the American planes. Though weak, they ran for an hour, covering two or three miles of dense woods. When they could run no longer, they stopped and rested on a large stump, realizing for the first time that they were free. “We looked at each other and I said, ‘We are free!’ We knew we were free, but what [were we] going to do now? We didn’t know what to do. First, we were bitter cold—it was so cold—and hungry. Well, we decided, let’s go see from the distance if we can see a farm or house. We’ll go in and we’ll ask, beg for bread and maybe they’ll give us some clothes.”

Pincus and his friends soon came to a farmhouse. They were relieved to find a sympathetic Czech farmer who provided them with old clothes and shoes, as well as food. The farmer, wary of being caught and killed by the Germans, who were looking for the three escapees, helped them dig a foxhole in the woods. They lived there for eighteen days, surviving on soup and bread that the farmer and others brought them each evening.

Finally, the farmer brought news they all were waiting to hear. “May the seventh, I remember…he came in. He told us, ‘You are free, the Americans are in town.’ Oh, my God, you  could feel the feeling. And I remember we went to a unit. We saw a tank unit, American unit, and we went there and we asked them if we can work for them—KP, you know—and we’ll be glad to do it for help because we had to have some food, something to eat. And they kept us for about a month. I’m telling you, they treated us royally, the Americans. They gave us uniforms. We looked like Americans, except we didn’t have the insignia.”

could feel the feeling. And I remember we went to a unit. We saw a tank unit, American unit, and we went there and we asked them if we can work for them—KP, you know—and we’ll be glad to do it for help because we had to have some food, something to eat. And they kept us for about a month. I’m telling you, they treated us royally, the Americans. They gave us uniforms. We looked like Americans, except we didn’t have the insignia.”

When the American unit returned to the United States two months later, Pincus and his friends were sent to Prague, even though the Americans wanted to take the three back to the United States with them. “You know these soldiers liked us so much they thought maybe [they could] smuggle us back into the United States. We went back all the way to Bremerhaven, believe it or not, with the unit. When it came to Bremerhaven we got on the ramp, on the ship—before we got on the ship everybody—we had the countdown, and they wouldn’t let us in. We had to—the unit, the company commander, he tried hard to smuggle us right in the border. They couldn’t do it because we didn’t have the count. [They] had the countdown and we didn’t have anything to prove who we are. So he took us on a jeep, took us back all the way to Czechoslovakia and dropped us off.”

Back in Prague, Pincus decided to go to the west part of Germany, because it was occupied by the Americans. He applied for a visa to the United States, which was finally approved in 1950. After arriving in New York, he was told by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society that he would be sent to Charleston, South Carolina. “I said, ‘But I came with all the friends of mine on the ship.’ We were what, fifteen hundred? Everybody goes to New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, you know. Here to Charleston; I’ve never heard of Charleston. Where is Charleston? Somewhere seven hundred miles away from New York. And I begged them, I pleaded with them, I said, ‘Can you please leave me here…with my friends? I [will] live in New York.’ He said, ‘I’m sorry, that’s the orders, you know how it is.’ So [they] sent me to Charleston. I had a rough time in Charleston; don’t think it was easy.”

Though not easy, Pincus was able to create a new life in Charleston. Six months after his arrival, he was drafted into the army and served  for two years. After returning home, he set up a successful business, Globe Furniture Company, at 502 King Street and married Renee (Fuchs) Fox, a fellow survivor he met at a Jewish war veteran dance. They had three children, and Pincus recovered the Jewish faith he’d lost during the war. “I didn’t believe in anything the first few years. But when I came to America, things had changed. You know, because my roots were religious—I was born and raised in an ultra-religious Jewish family. The first five years I said, ‘Well, there is no God, if he could do something like that.’ But, when I came here I married, things had changed. You know, you go back to your roots. And I believe now. I became a believer, back to my roots, and we believe. I brought up my children—I sent them all to Hebrew Institute and they all were raised religious, they have religion.”

for two years. After returning home, he set up a successful business, Globe Furniture Company, at 502 King Street and married Renee (Fuchs) Fox, a fellow survivor he met at a Jewish war veteran dance. They had three children, and Pincus recovered the Jewish faith he’d lost during the war. “I didn’t believe in anything the first few years. But when I came to America, things had changed. You know, because my roots were religious—I was born and raised in an ultra-religious Jewish family. The first five years I said, ‘Well, there is no God, if he could do something like that.’ But, when I came here I married, things had changed. You know, you go back to your roots. And I believe now. I became a believer, back to my roots, and we believe. I brought up my children—I sent them all to Hebrew Institute and they all were raised religious, they have religion.”

After Pincus retired from Globe Furniture in the 1980s, he began to speak publicly about his experiences. Many schoolchildren first learned about the Holocaust through his presentations. “The main thing is education. I think it’s very important to educate the future generations. They should know [about] it, because ignorance only brings hate—creates hate—and if people know what happened and learn about it, it may prevent another Holocaust.”

Source: Pincus Kolender papers (Mss 1065-014), Jewish Heritage Collection, Addlestone Library Special Collections